Police officers routinely deal with people behaving at their worst. Frequent encounters with verbally abusive and sometimes physically combative citizens also come with the badge.

Despite these experiences, the Pew Research Center survey finds that a majority of officers retain a generally positive view of the public. About seven-in-ten reject the assertion that most people can’t be trusted, and a similar share believes that most people respect the police. These opinions, if anything, have grown somewhat more positive in recent years despite the national outcry over police methods and behaviors that followed a series of recent, highly publicized deaths of black men at the hands of law enforcement officers.

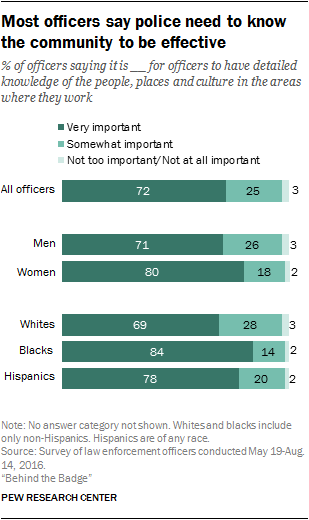

Rather than viewing the neighborhoods where they work as hostile territory, about seven-in-ten officers say at least some or most of the residents share their values. More than nine-in-ten believe it is important for an officer to know the people, places and the culture in the areas where they work in order to be effective at their job.

About nine-in-ten officers (91%) also say police have an excellent or good relationship with whites in their communities. But just 56% rate the relationship between police and blacks positively, while seven-in-ten report good relations with Hispanics. These perceptions differ dramatically depending on the race or ethnicity of the officer. For example, six-in-ten white officers characterize police relations with blacks in their areas as excellent or good, a view shared by only 32% of black officers.

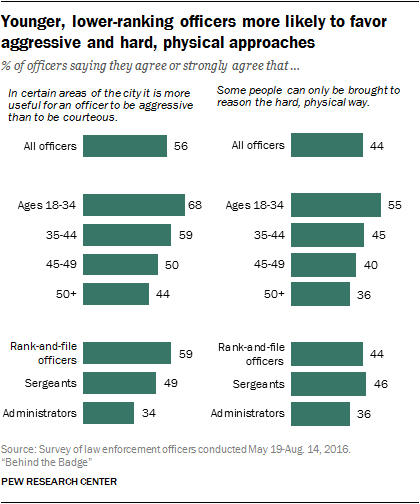

The survey also finds that officers are divided over the use of more aggressive and potentially more controversial methods to deal with some people or to use in some neighborhoods in their communities. A modest majority (56%) agree that aggressive tactics are more effective than a more courteous approach in certain areas of the city, but 44% disagree with this premise. Another 44% agree or strongly agree that some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way. Younger, less experienced and lower ranking officers are significantly more likely to favor these more confrontational approaches than older, more experienced department administrators.

The survey also finds that police work takes an emotional toll on many officers. A 56% majority say they have become more callous toward people since they started their job. This perceived change in outlook is closely linked to increased support for aggressive or physically punishing tactics. In addition, officers who say they have become more callous on the job report significantly higher levels of work-related anger and frustration than other officers. They also are more likely to have fought or struggled with a suspect who was resisting arrest in the past month or to have fired their service weapon sometime in their career.

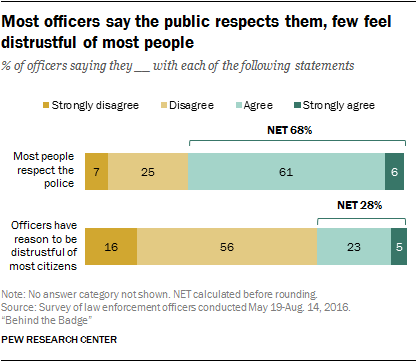

Roughly two-thirds of all officers agree (61%) or strongly agree (6%) that most people respect the police. About seven-in-ten (72%) reject the statement that “Officers have reason to be distrustful of most citizens.”

Comparisons with earlier surveys by the National Police Research Platform (NPRP) find that these views of the public have not grown more negative in the wake of recent deadly encounters involving police and black men. If anything, these data suggest police views of the public have gotten more favorable in the past year and a half.

In the NPRP survey conducted in September 2013 to January 2014, six-in-ten officers said most of the public respects the police. A somewhat smaller share (55%) expressed the same opinion in a NPRP survey conducted in October 2014 to February 2015, months after the Michael Brown shooting. But since then, the share who says police are respected has rebounded to 68%.

The mistrust measure has varied less in recent years. In the 2013-14 survey, 67% of officers disagreed that officers have reason to be distrustful of most citizens, a view shared by 69% of officers in 2014-15 and 72% in the latest survey.

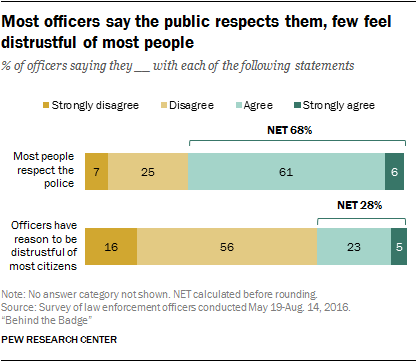

These views differ significantly by rank. Rank-and-file officers – a group largely composed of the men and women with the greatest contact with average citizens – have a significantly less favorable view of the public than do administrators. About two-thirds of rank-and-file officers (65%) but 86% of administrators believe that most people respect the police.

Similarly, 70% of rank-and-file officers but 86% of administrators disagree or strongly disagree that police have reason to distrust most people.

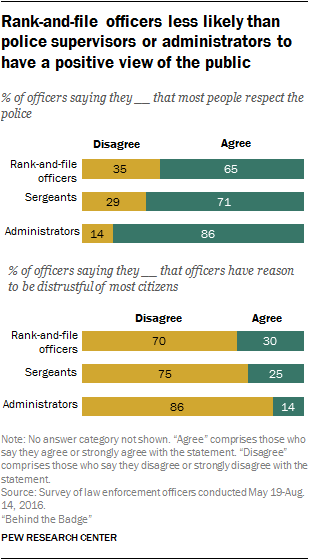

Most officers agree that in order to be effective, police need to understand the people in the neighborhoods they patrol. About seven-in-ten (72%) say it is very important for an officer to have detailed knowledge of the people, places and culture in the areas where they work, while a quarter say it is somewhat important. Only 3% say knowledge of the neighborhoods they patrol is not too or not at all important.

Yet the degree to which officers value local knowledge varies significantly by the officer’s race and gender. Fully 84% of black officers and 78% of Hispanics say knowledge of the people, places and culture of the neighborhoods they patrol is very important to be effective at their job, a view shared by 69% of whites. Female officers also are more likely than males to place a premium on local knowledge (80% vs. 71%).

Overall, about seven-in-ten officers say at least some (59%) or most or nearly all (11%) of the people in the neighborhoods where they routinely work share their values and beliefs.

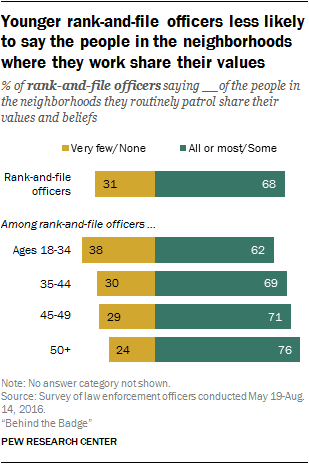

Significant differences emerge when these results are broken down by the officer’s rank: About two-thirds of rank-and-file officers (68%) believe that some or most of the people living in their patrol areas share their beliefs. By contrast, three-quarters of sergeants and 85% of administrators say the same thing.

When the analysis is limited to rank-and-file officers – the group that arguably has the most direct daily contact with citizens – views differ significantly within key demographic groups. Most notably, younger rank-and-file officers and those in larger departments are less likely than older officers or those in small police departments to say they share common values and beliefs with at least some of the people in the areas they patrol.

About six-in-ten rank-and-file officers (62%) ages 18 to 34 say some or most of the people in the neighborhoods where they work share their beliefs and attitudes. By contrast, about three-quarters (76%) of rank-and-file officers ages 50 and older express a similar view.

Rank-and-file officers in larger departments also are less likely to share values with the people in the areas where they patrol. Eight-in-ten rank-and-file officers working in departments with fewer than 300 sworn personnel say they share values and beliefs with at least some of the people they patrol. By contrast, about six-in-ten (62%) rank-and-file officers in departments with 2,600 or more sworn personnel say the same. (This difference may not be surprising. Larger departments typically serve urban areas with a more diverse set of neighborhoods than smaller communities. These urban neighborhoods often can be home to various nationalities and racial, ethnic, language and religious groups with attitudes and beliefs that may be very different from those of the rank-and-file officer. 10 )

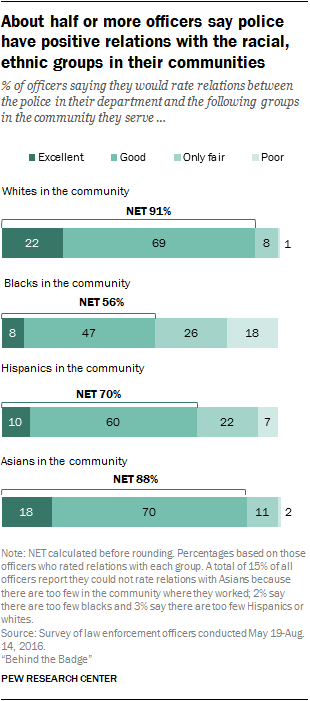

About half or more of all officers say their departments have excellent or good relations with major racial and ethnic groups in the communities where they work. This overall positive assessment varies considerably by the racial/ethnic group and also by the race and ethnicity of the officer. Black officers in particular are significantly less likely than white or Hispanic officers to rate relations with minority groups in their community favorably. (Note: The percentages are based on only those officers who offered a rating.)

Overall, about nine-in-ten officers (91%) characterize relations between police and whites in their communities as excellent (22%) or good (69%). By contrast, 56% of all officers have a similarly positive view of relations between police and the black community (8% say relations are excellent, while 47% say they are good). Seven-in-ten say relations with Hispanics are positive, and 88% say the same about Asians.

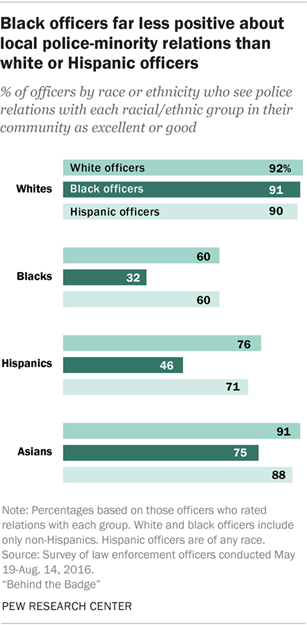

About nine-in-ten white, black and Hispanic officers agree that police and whites in their communities have good relations. But striking differences emerge when the focus shifts to how black, white and Hispanic officers view police-minority relations in their communities.

Only about a third of all black officers (32%) say relations between police and blacks in their community are excellent or good, while about twice as many (68%) characterize police-black relations as only fair or poor.

By contrast, six-in-ten white and Hispanic officers report that police-black relations in the communities they serve are excellent or good.

Views also diverge along racial lines when the focus turns to how black, white and Hispanic officers view police-Hispanic relations. Roughly three-quarters of white officers (76%) and 71% of Hispanic officers say police in their communities have excellent or good relations with Hispanics. By contrast, only 46% of black officers share that positive assessment, while 54% characterize relations between police and Hispanics as only fair or poor.

A similar but more muted pattern is apparent on views of police relations with Asians in their community. About nine-in-ten white and Hispanic officers (91% and 88%, respectively) say relations between police and Asians are excellent or good, while 75% of black officers agree.

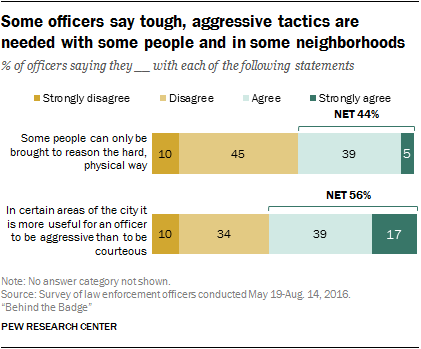

To measure the extent to which officers endorse the use of aggressive tactics in some situations over less potentially provocative techniques, the survey asked officers how much they agreed or disagreed with two statements. The first statement read, “In certain areas of the city it is more useful for an officer to be aggressive than to be courteous.” The second measured support for the assertion that “some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way.”

Overall, the survey finds that a narrow majority (56%) of officers feel that in some neighborhoods being aggressive is more effective than being courteous. A smaller but still substantial share (44%) agrees or strongly agrees that hard, physical tactics are necessary to deal with some people, while 55% disagree.

The survey also finds that younger and less senior officers are more likely than older officers or administrators to favor more potentially provocative methods. About two-thirds (68%) of officers younger than 35 favor being aggressive over being courteous in some neighborhoods. By contrast, the share supporting aggressiveness over courtesy falls steadily in each age group to 44% among officers 50 and older. And while a narrow majority of younger officers (55%) approve of using a hard, physical approach with some people, support for rough tactics declines to about a third (36%) for officers 50 and older.

Significant differences in views on both questions emerge when the analytic focus shifts to the officer’s rank. About six-in-ten rank-and-file officers (59%) support using aggressive tactics in place of courtesy in some neighborhoods, a view shared by only 34% of department administrators. To a lesser extent, rank-and-file officers also are more likely than department administrators to favor harsh, physical methods in dealing with certain people (44% vs. 36%). Sergeants (46%) also are more likely than administrators to support hard, physical tactics.

The clear differences in the views of lower-ranking officers and more senior administrators raise this question: Since department administrators are older than rank-and-file officers (median age 49 vs. 41), could these differences in attitudes mainly be due to factors associated with officers’ rank or tenure and not their age?

The answer is no. When only the views of rank-and-file officers are examined, the same age pattern is evident: Fully 69% of rank-and-file officers younger than 35 favored aggressive tactics over a courteous approach, compared with 48% of rank-and-file officers 50 and older. Similarly, slightly more than half (55%) of rank-and-file officers under the age of 35 agreed that hard, physical methods are needed for some people, compared with 35% of rank-and-file officers 50 and older.

The relationship between support for harsh tactics and an officer’s years of police experience follows a similar though more complex pattern because age is closely correlated with police experience. Once differences by age are accounted for in the analysis, there are no significant differences in views based on experience. For example, more than half (55%) of rank-and-file officers younger than 35 with less than 10 years of experience favor harsher measures for some people – and so does about the same proportion (54%) of those with 10 or more years of service.

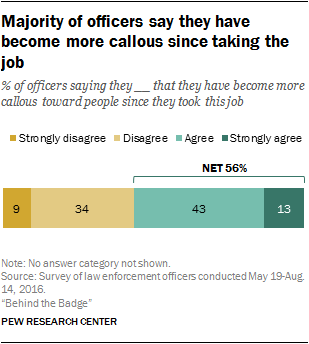

Police work can be emotionally difficult, and it hardens many officers. According to the survey, a narrow majority of the police (56%) say they have become more callous toward people since taking their job, a view that is significantly more likely to be held by whites and younger officers than by blacks or older department members.

Overall, the survey finds that 13% strongly agree and an additional 43% agree that they have become more callous toward people since taking the job. About a third (34%) disagree, while 9% strongly disagree.

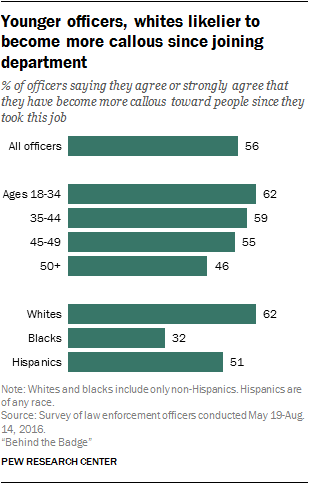

Younger officers are particularly likely to say they have become more callous, a view shared by 62% of officers younger than 35 but only 46% of those 50 or older.

The differences are even greater when the views of black and white officers are compared. Only about a third (32%) of black officers but about twice the share of whites (62%) report they have become more callous since taking the job.

Hispanic officers fall between white and black officers on this question. About half (51%) of Hispanic officers say they have grown more callous, a significantly larger share than among blacks but significantly smaller than the proportion of whites.

Comparisons to the results of previous NPRP police surveys suggest little significant variation in the share of officers who report becoming more callous. In the 2013-14 survey, the number stood at 53%, while in the 2014-15 poll, 59% reported growing more callous since taking this job compared with 56% in the latest poll.

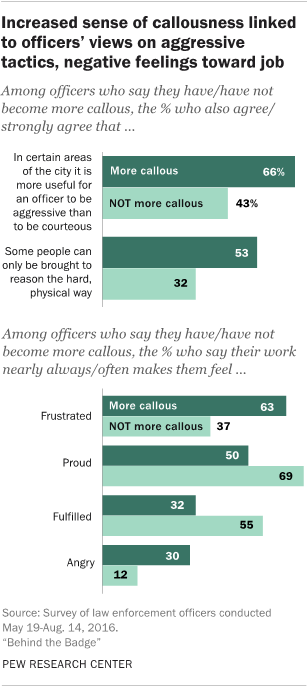

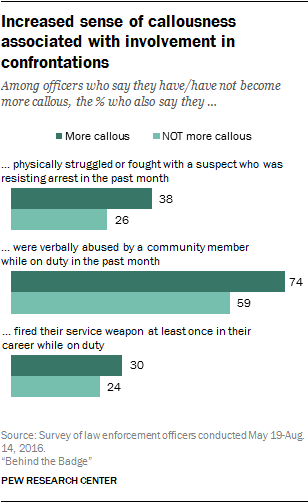

The survey finds that officers who feel they have grown more callous since starting their job are also more likely to endorse the use of aggressive or physically harsh tactics in some situations or in some parts of the community than officers who say they have not grown more callous. Officers who say they have grown more callous are also more likely than their colleagues who say they have not to say they are frequently angered or frustrated by their jobs. They also are more likely to have been involved in a physical or verbal confrontation with a citizen in the past month or to have fired their service weapon sometime in their careers.

About two-thirds (66%) of those who self-report having become more callous also agree that it is more useful in certain neighborhoods for an officer to be aggressive rather than to be courteous. By contrast, roughly four-in-ten (43%) of those who have not become more callous say this. Similarly, about half of officers (53%) who say they have become more callous agree or strongly agree that hard, physical methods are the only way to deal with some individuals, a view shared by 32% of those who say they have not become more callous.

It is difficult to determine from these data whether increased callousness is a primary cause or a consequence of feelings of anger or frustration, or the source of attitudes toward aggressive tactics. It could be that an increasingly callous outlook breeds anger and aggression in some officers. It could also be that repeated exposure to confrontations with citizens or frustrations on the job leads an officer to become more unfeeling.

However, the data suggest that these feelings and behaviors are related. For example, the sense of having become more callous on the job is associated with how these officers feel about their work, the survey finds. Those who say they have become more callous are about twice as likely as those who say they have not to say their job nearly always or often makes them feel angry (30% vs. 12%). They also are far more likely to nearly always or often feel frustrated by their job (63% compared with 37% among those who say they have not become more callous since taking their job).

By the same token, those who say they have grown more callous are significantly less likely than other officers to say their job nearly always or often makes them feel fulfilled (32% vs. 55%) and are less likely to say they often feel proud (50% vs. 69%) about their work.

An officer’s sense that he or she has grown more callous on the job also is associated with a range of experiences on the streets. While this analysis does not attempt to determine whether increased callousness is a primary cause of these behaviors, these data suggest they are related.

Among those officers who say they have become more callous toward people, roughly four-in-ten (38%) also report they had physically struggled or fought with a suspect who was resisting in the past month. By contrast, about a quarter (26%) of those who say they have not become more insensitive were involved in a physical altercation during an arrest in the past month.

At the same time, about three-quarters (74%) of those who say they have grown more callous also say they were verbally abused by a community member in the past month compared with 59% of other officers. Three-in-ten officers who say they have grown more callous also report firing their service weapons sometime during their police careers. By contrast, 24% of other police officers say this.