Do you like poems?

If you do, try a haiku.

It’s a lovely form!

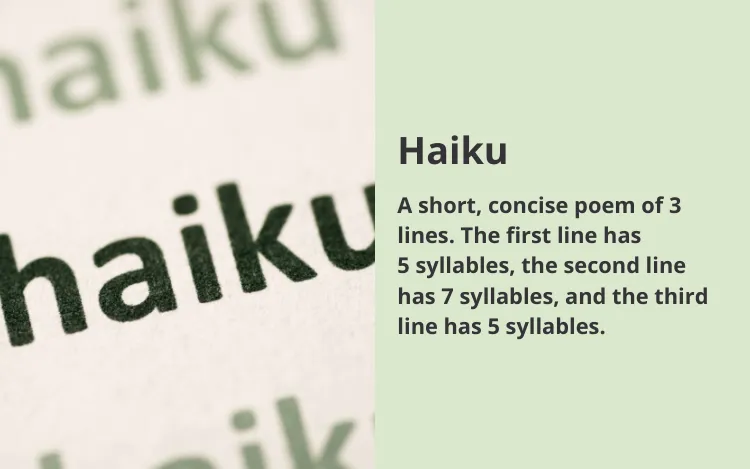

Haiku are short poems that follow a specific three-line format, where the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and the last line has five syllables again—just like the first line.

Read on to learn what a haiku is and how you can write one of your own.

A haiku is a short, concise poem that consists of three lines. Traditionally, the first line has five syllables, the second line has seven, and the final line has five.

Each haiku is so short and succinct that you need to choose each syllable carefully. The art of haiku is all about expressing as much as possible in very few words.

This form of poetry originated in Japan. In its earliest form, it was known as hokku.

Japanese poets have been writing hokku for centuries, originally as parts of a longer collaborative poem known as a renga, which sometimes consisted of more than a hundred lines. Poets worked in groups of two or three to take turns composing three-line stanzas and two-line stanzas until they created a complete renga .

Around the 17th century, poets began writing short self-contained poems in the same form as the opening hokku of a renga. Late in the 19th century, renowned poet Masaoka Shiki renamed the stand-alone hokku to haiku .

Most traditional haiku describe a moment in time that captures the beauty or power of the natural world. Classic Japanese poets often used haiku to describe seasonal changes or other natural phenomena.

These days, people all over the world write haiku in various languages about countless different themes. Many poets even break the standard rules of how many syllables each line needs to have, choosing to adhere to the spirit of a haiku rather than the technical rules a haiku usually follows.

The traditional structure of an English haiku consists of three nonrhyming lines with the following syllable counts:

That’s it! If you stick to these syllable counts, you’ll be writing a haiku in no time. The hard part is choosing words that fit perfectly into this format.

Another important decision involves choosing the subject of your haiku.

If you want to stick with the traditional version of haiku, you should describe a moment of time that’s related to the power of nature. Traditional Japanese haiku are supposed to include a kigo , which is a seasonal reference.

Many haiku also juxtapose two distinct images, such as a small cricket with a large mountain or a laughing child with a bitter storm.

Ultimately, you can also use the form to write about anything that resonates with you, the same way you would use any other poetic form. You can write a haiku about love, death, parenthood, corporate office culture, or any other theme you care about.

The rules of haiku format vary between languages, since each language has distinct grammar, punctuation, and formatting conventions. There are some aspects of Japanese haiku format that don’t apply to English haiku format.

For example, traditional Japanese haiku include at least one kireji , which means “cutting word.” The purpose of a kireji is to make a “cut” in a sentence, which cements the end of a stream of thought or creates a pause between two separate ideas.

There’s no exact equivalent to kireji in the English language, so the English haiku format doesn’t include this rule. If you want, you can try to replicate the effect of kireji by using a punctuation mark that creates a “cut” in a sentence, such as an exclamation point, an em dash, or an ellipsis.

The best way to learn poetry is by reading masterful haiku examples so you can learn from the greats.

Four of the greatest haiku masters of all time are Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694), Yosa Buson (1716–1784), Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828), and Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902).

Let’s look at a few examples of Japanese haiku written by these four masters.

“The Old Pond” by Matsuo Bashō

An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.

You can clearly see the contrasting images in this haiku by Matsuo Bashō, which describes a moment in nature. The pond in the poem is silent and still, while the frog is full of motion.

These two images are separated by the kireji, which are represented in the English translation by the ellipsis and the em dash.

One common interpretation of this poem is that Bashō is using the pond as a metaphor for the human mind. External stimuli, like the frog, can momentarily disrupt a mind at rest, but soon, the mind returns to its original state.

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.